3.5: Absolute-Value Functions

- Page ID

- 34412

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)To graph absolute-value functions, choose small values of \(x\), and compute the value of \(f(x)\) from the given function to create ordered pairs. Three ordered pairs is the minimum amount needed to graph an absolute value function. Be careful, because one ordered pair must represent the vertex, the point where the left and right sides of the function meet. To correctly graph the shape of the absolute-value function, the vertex must be found.

\(f(x) = a\vert x − h\vert+ k\) General Form of an Absolute-Value Function, with vertex \((h,k)\)

- \(a\) determines both the width and the orientation (facing up or down) of the function.

- \(h\) is the horizontal shift from the origin.

- \(k\) is the vertical shift from the origin.

Start by identifying the ordered pair of the vertex, and then find one ordered pair to the left of the origin, and to the right of the origin. Choose an x-value one unit to the left of the x-value of the origin, calculate \(f(x)\) and then choose an x-value one unit to the right of the x-value of the origin and calculate \(f(x)\). The graph will resemble a \(V\), either facing upward or downward, depending on the sign of \(a\).

Create a table of solutions and graph the following absolute-value function:

\(f(x) = \vert x − 4\vert\)

Solution

Comparing this function to the general form for absolute-value functions (shown above), \(a = 1\), \(h = 4\), \(k = 0\). The vertex is \((h, k)\) or \((4, 0)\).

To find two more ordered pairs, choose \(x = 3\) and \(x = 5\), then compute values of \(f(x)\).

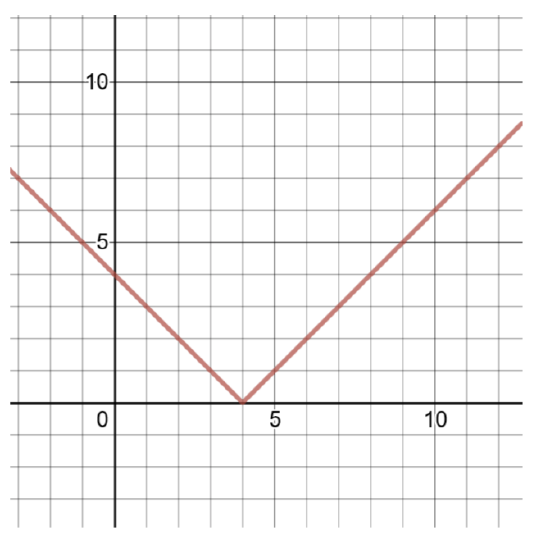

Figure 4.5.1

Figure 4.5.1

| \(x\) | \(f(x)\) |

|---|---|

| 3 | \(f(3) = \vert 3 − 4\vert = \vert − 1\vert = 1\) |

| 4 | \(f(4) = \vert 4 − 4\vert = \vert 0\vert = 0\) |

| 5 | \(f(5) = \vert 5 − 4\vert = \vert 1\vert = 1\) |

Create a table of solutions and graph the following absolute-value function:

\(g(x) = \vert x + 2\vert − 5\)

Solution

Comparing this function to the general form for absolute-value functions (shown above), \(a = 1\), \(h = −2\), \(k = −5\). The vertex is (h, k)\) or \((−2, −5)\).

To find two more ordered pairs, choose \(x = −3\) and \(x = −1\), then compute values of \(g(x)\)

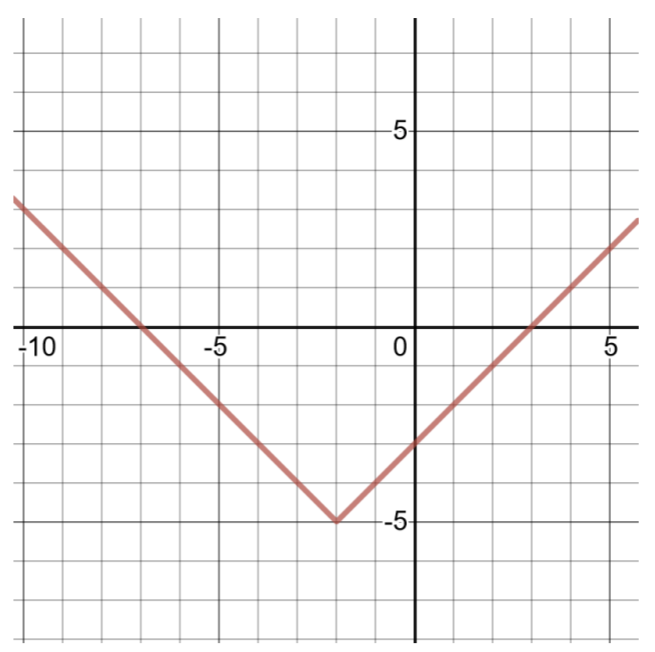

Figure 4.5.2

Figure 4.5.2

| Table of Solutions for \(g(x) = \vert x + 2\vert − 5\) | |

| \(x\) | \(g(x)\) |

| -3 | \(g(−3) = \vert − 3 + 2\vert − 5 = \vert − 1\vert − 5 = 1 − 5 = −4\) |

| -2 | \(g(−2) = \vert − 2 + 2\vert − 5 = \vert 0\vert − 5 = 0 − 5 = −5\) |

| -1 | \(g(−1) = \vert − 1 + 2\vert − 5 = \vert 1\vert − 5 = 1 − 5 = −4\) |

Create a table of solutions and graph the following absolute-value function:

\(h(x) = 3\vert x − 5\vert + 1\)

Solution

Comparing this function to the general form for absolute-value functions (shown above), \(a = 3\), \(h = 5\), \(k = 1\). The vertex is \((h, k)\) or \((5, 1)\).

To find two more ordered pairs, choose \(x = 4\) and \(x = 6\), then compute values of \(h(x)\).

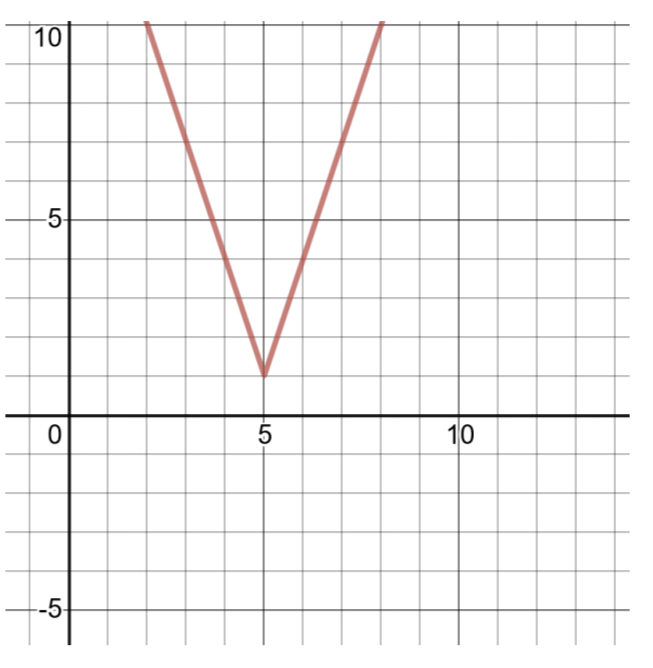

Figure 4.5.3

Figure 4.5.3

| Table of Solutions for \(h(x) = 3\vert x − 5\vert + 1\) | |

| \(x\) | \(h(x)\) |

| 4 | \(g(−3) = \vert − 3 + 2\vert − 5 = \vert − 1\vert − 5 = 1 − 5 = −4\) |

| 5 | \(g(−2) = \vert − 2 + 2\vert − 5 = \vert 0\vert − 5 = 0 − 5 = −5\) |

| 6 | \(g(−1) = \vert − 1 + 2\vert − 5 = \vert 1\vert − 5 = 1 − 5 = −4\) |

Create a table of solutions and graph the following absolute-value function:

\(h(x) = \dfrac{1}{2} \vert x − 2\vert + 3\)

Solution

Comparing this function to the general form for absolute-value functions (shown above), \(a = \dfrac{1}{2} \), \(h = 2\), \(k = 3\). The vertex is \((h, k)\) or \((2, 3)\).

To find two more ordered pairs, choose \(x = 1\) and \(x = 3\), then compute values of \(h(x)\).

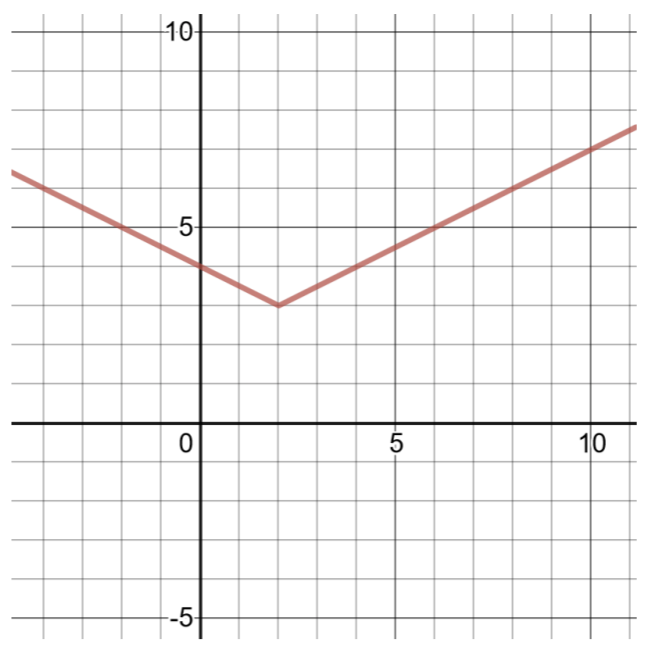

Figure 4.5.4

Figure 4.5.4

| Table of Solutions for \(h(x) = \dfrac{1}{2} \vert x − 2\vert + 3\) | |

| \(x\) | \(h(x)\) |

| 1 | \(h(1) = \dfrac{1}{2} \vert 1 − 2\vert + 3 = \dfrac{1}{2} \vert − 1\vert + 3 = \dfrac{1}{2} (1) + 3 = 3\dfrac{1}{2}\) |

| 2 | \(h(2) = \dfrac{1}{2} \vert 2 − 2\vert + 3 = \dfrac{1}{2} \vert 0\vert + 3 = 0 + 3 = 3\) |

| 3 | \(h(3) = \dfrac{1}{2} \vert 3 − 2\vert + 3 = \dfrac{1}{2} \vert 1\vert + 3 = \dfrac{1}{2} (1) + 3 = 3\dfrac{1}{2}\) |

Create a table of solutions and graph the following absolute-value functions:

- \(f(x) = \vert x + 6\vert\)

- \(g(x) = \dfrac{1}{3} \vert x − 3\vert + 5\)

- \(h(x) = 4\vert x + 2\vert + 2\)

- \(f(x) = \vert x − 1\vert − 5\)