8.3: Power and Sum Rules for Derivatives

- Page ID

- 26568

In the next few sections, we’ll get the derivative rules that will let us find formulas for derivatives when our function comes to us as a formula. This is a very algebraic section, and you should get lots of practice. When you tell someone you have studied calculus, this is the one skill they will expect you to have.

Building Blocks

These are the simplest rules – rules for the basic functions. We won't prove these rules; we'll just use them. But first, let's look at a few so that we can see they make sense.

Find the derivative of \( y=f(x)=mx+b \).

Solution

This is a linear function, so its graph is its own tangent line! The slope of the tangent line, the derivative, is the slope of the line: \[f'(x)=m\nonumber \]

The derivative of a linear function is its slope.

Find the derivative of \( f(x)=135 \).

Solution

Think about this one graphically, too. The graph of \(f(x)\) is a horizontal line. So its slope is zero: \[f'(x)=0\nonumber \]

The derivative of a constant is zero.

Find the derivative of \( f(x)=x^2 \).

Solution

Recall the formal definition of the derivative: \[f'(x)=\lim\limits_{h\to 0} \frac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}.\nonumber \]

Using our function \( f(x)=x^2 \), \( f(x+h)=(x+h)^2=x^2+2xh+h^2 \).

Then \[ \begin{align*} f'(x) & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0} \frac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}\\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0} \frac{x^2+2xh+h^2-x^2}{h}\\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0} \frac{2xh+h^2}{h}\\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0} \frac{h(2x+h)}{h}\\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0} (2x+h)\\ & = 2x \end{align*} \nonumber \]

From all that, we find that \( f'(x)=2x \).

Luckily, there is a handy rule we use to skip using the limit:

The derivative of \( f(x)=x^n \) is \[f'(x)=nx^{n-1}.\nonumber \]

Find the derivative of \( g(x)=4x^3 \).

Solution

Using the power rule, we know that if \( f(x)=x^3 \), then \( f'(x)=3x^2 \). Notice that \(g\) is 4 times the function \(f\). Think about what this change means to the graph of \(g\) – it’s now 4 times as tall as the graph of \(f\). If we find the slope of a secant line, it will be \( \frac{\Delta g}{\Delta x}= \frac{4\Delta f}{\Delta x} =4\frac{\Delta f}{\Delta x} \); each slope will be 4 times the slope of the secant line on the \(f\) graph. This property will hold for the slopes of tangent lines, too: \[\frac{d}{dx}\left(4x^3\right)=4\frac{d}{dx}\left(x^3\right)=4\cdot 3x^2=12x^2.\nonumber \]

Constants come along for the ride, i.e., \( \frac{d}{dx}\left( kf\right)=kf'.\)

Here are all the basic rules in one place.

In what follows, \(f\) and \(g\) are differentiable functions of \(x\).

Constant Multiple Rule

\[ \frac{d}{dx}\left( kf\right)=kf'\nonumber \]

Sum and Difference Rule

\[\frac{d}{dx}\left(f\pm g\right)=f' \pm g'\nonumber \]

Power Rule

\[\frac{d}{dx}\left(x^n\right)=nx^{n-1}\nonumber \]

Special cases: \[\frac{d}{dx}\left(k\right)=0 \quad \text{(Because \( k=kx^0 \).)}\nonumber \] \[\frac{d}{dx}\left(x\right)=1 \quad \text{(Because \( x=x^1 \).)}\nonumber \]

Exponential Functions

\[\frac{d}{dx}\left(e^x\right)=e^x\nonumber \] \[\frac{d}{dx}\left(a^x\right)=\ln(a)\,a^x\nonumber \]

Natural Logarithm

\[\frac{d}{dx}\left(\ln(x)\right)=\frac{1}{x}\nonumber \]

The sum, difference, and constant multiple rule combined with the power rule allow us to easily find the derivative of any polynomial.

Find the derivative of \( p(x)=17x^{10}+13x^8-1.8x+1003 \).

Solution

\[ \begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx}\left( 17x^{10}+13x^8-1.8x+1003 \right) & = \frac{d}{dx}\left( 17x^{10} \right)+\frac{d}{dx}\left( 13x^8 \right)-\frac{d}{dx}\left( 1.8x \right)+\frac{d}{dx}\left( 1003 \right)\\ & = 17\frac{d}{dx}\left( x^{10} \right)+13\frac{d}{dx}\left( x^8 \right)-1.8\frac{d}{dx}\left( x \right)+\frac{d}{dx}\left( 1003 \right)\\ & = 17\left(10x^9\right)+13\left(8x^7\right)-1.8\left(1\right)+0\\ & = 170x^9+104x^7-1.8 \end{align*} \nonumber \]

You don't have to show every single step. Do be careful when you're first working with the rules, but pretty soon you’ll be able to just write down the derivative directly:

Find \(\frac{d}{dx}\left( 17x^2-33x+12 \right)\).

Solution

Writing out the rules, we'd write \[\frac{d}{dx}\left( 17x^2-33x+12 \right)=17(2x)-33(1)+0=34x-33.\nonumber \]

Once you're familiar with the rules, you can, in your head, multiply the 2 times the 17 and the 33 times 1, and just write \[\frac{d}{dx}\left( 17x^2-33x+12 \right)=34x-33.\nonumber \]

The power rule works even if the power is negative or a fraction. In order to apply it, first translate all roots and basic rational expressions into exponents:

Find the derivative of \( y=3\sqrt{t}-\frac{4}{t^4}+5e^t \).

Solution

The first step is translate into exponents: \[y=3\sqrt{t}-\frac{4}{t^4}+5e^t=3t^{1/2}-4t^{-4}+5e^t\nonumber \]

Now you can take the derivative: \[ \begin{align*} \frac{d}{dt}\left( 3t^{1/2}-4t^{-4}+5e^t \right) & = 3\left(\frac{1}{2}t^{-1/2}\right)-4\left(-4t^{-5}\right)+5\left(e^t\right) \\ & = \frac{3}{2}t^{-1/2}+16t^{-5}+5e^t \end{align*} \nonumber \]

If there is a reason to, you can rewrite the answer with radicals and positive exponents: \[y'= \frac{3}{2}t^{-1/2}+16t^{-5}+5e^t= \frac{3}{2\sqrt{t}}+\frac{16}{t^5}+5e^t\nonumber \]

Be careful when finding the derivatives with negative exponents.

We can immediately apply these rules to solve the problem we started the chapter with - finding a tangent line.

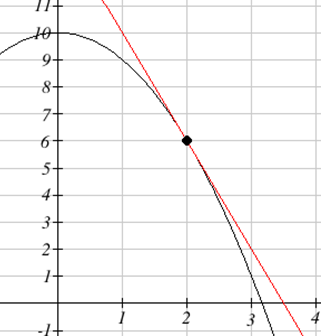

Find the equation of the line tangent to \( g(t)=10-t^2 \) when \(t = 2\).

Solution

The slope of the tangent line is the value of the derivative. We can compute \( g'(t)=-2t \). To find the slope of the tangent line when \(t = 2\), evaluate the derivative at that point. The slope of the tangent line is -4.

To find the equation of the tangent line, we also need a point on the tangent line. Since the tangent line touches the original function at \(t = 2\), we can find the point by evaluating the original function: \( g(2)=10-2^2=6 \). The tangent line must pass through the point (2, 6).

Using the point-slope equation of a line, the tangent line will have equation \( y-6=-4(t-2) \). Simplifying to slope-intercept form, the equation is \( y=-4t+14 \).

Graphing, we can verify this line is indeed tangent to the curve:

We can also use these rules to help us find the derivatives we need to interpret the behavior of a function.

In a memory experiment, a researcher asks the subject to memorize as many words from a list as possible in 10 seconds. Recall is tested, then the subject is given 10 more seconds to study, and so on. Suppose the number of words remembered after \(t\) seconds of studying could be modeled by \( W(t)=4t^{2/5} \). Find and interpret \( W'(20) \).

Solution

\( W'(t)=4\cdot \frac{2}{5}t^{-3/5}=\frac{8}{5}t^{-3/5} \), so \( W'(20)=\frac{8}{5}(20)^{-3/5}\approx 0.2652 \).

Since \(W\) is measured in words, and \(t\) is in seconds, \(W'\) has units words per second. \( W'(20)\approx 0.2652 \) means that after 20 seconds of studying, the subject is learning about 0.27 more words for each additional second of studying.

Business and Economics Terms

Next we will delve more deeply into some business applications. To do that, we first need to review some terminology.

Suppose you are producing and selling some item. The profit you make is the amount of money you take in minus what you have to pay to produce the items. Both of these quantities depend on how many you make and sell. (So we have functions here.) Here is a list of definitions for some of the terminology, together with their meaning in algebraic terms and in graphical terms.

Your cost is the money you have to spend to produce your items.

The Fixed Cost (FC) is the amount of money you have to spend regardless of how many items you produce. FC can include things like rent, purchase costs of machinery, and salaries for office staff. You have to pay the fixed costs even if you don’t produce anything.

The Total Variable Cost (TVC) for \(q\) items is the amount of money you spend to actually produce them. TVC includes things like the materials you use, the electricity to run the machinery, gasoline for your delivery vans, maybe the wages of your production workers. These costs will vary according to how many items you produce.

The Total Cost (TC, or sometimes just C) for \(q\) items is the total cost of producing them. It’s the sum of the fixed cost and the total variable cost for producing \(q\) items.

The Average Cost (AC) for \(q\) items is the total cost divided by \(q\), or

\[AC(q) = \frac{TC}{q}\nonumber \]

You can also talk about the average fixed cost, \(\frac{FC}{q}\), or the average variable cost, \(\frac{TVC}{q}\).

The Marginal Cost (MC) at \(q\) items is the cost of producing the next item. Really, it’s \[MC(q) = TC(q + 1) - TC(q).\nonumber \] In many cases, though, it’s easier to approximate this difference using calculus (see Example 1 below). And some sources define the marginal cost directly as the derivative, \[MC(q) = TC'(q).\nonumber \] In this course, we will use both of these definitions as if they were interchangeable.

The units on marginal cost is cost per item.

For the purposes of this course, if a question asks for marginal cost, revenue, profit, etc., compute it using the derivative if possible, unless specifically told otherwise.

Why is it okay that there are two definitions for Marginal Cost (and Marginal Revenue, and Marginal Profit)?

We have been using slopes of secant lines over tiny intervals to approximate derivatives. In this example, we’ll turn that around – we’ll use the derivative to approximate the slope of the secant line.

Notice that the “cost of the next item” definition is actually the slope of a secant line, over an interval of 1 unit: \[MC(q) = C(q + 1) - 1 = \frac{C(q+1)-1}{1}.\nonumber \]

So this is approximately the same as the derivative of the cost function at q: \[MC(q) = C'(q).\nonumber \]

In practice, these two numbers are so close that there’s no practical reason to make a distinction. For our purposes, the marginal cost is the derivative is the cost of the next item.

The table shows the total cost (TC) of producing \(q\) items.

| Items, \( q \) | TC |

| 0 | $20,000 |

| 100 | $35,000 |

| 200 | $45,000 |

| 300 | $53,000 |

- What is the fixed cost?

- When 200 items are made, what is the total variable cost? The average variable cost?

- When 200 items are made, estimate the marginal cost.

Solution

- The fixed cost is $20,000, the cost even when no items are made.

- When 200 items are made, the total cost is $45,000. Subtracting the fixed cost, the total variable cost is $45,000 - $20,000 = $25,000.

The average variable cost is the total variable cost divided by the number of items, so we would divide the $25,000 total variable cost by the 200 items made. $25,000/200 = $125. On average, each item had a variable cost of $125.

- We need to estimate the value of the derivative, or the slope of the tangent line at \(q = 200\). Finding the secant line from \(q=100\) to \(q=200\) gives a slope of \[ \frac{45,000-35,000}{200-100}=100.\nonumber \]

Finding the secant line from \(q=200\) to \(q=300\) gives a slope of \[\frac{53,000-45,000}{300-200}=80.\nonumber \]

We could estimate the tangent slope by averaging these secant slopes, giving us an estimate of $90/item.

This tells us that after 200 items have been made, it will cost about $90 to make one more item.

The cost to produce \(x\) items is \(C(x) = \sqrt{x}\) hundred dollars.

- What is the cost for producing 100 items? 101 items? What is cost of the 101st item?

- Calculate \(C '(x)\) and evaluate \(C '\) at \(x = 100\). How does \(C '(100)\) compare with the last answer in Part a?

Solution

- \(C(100) =\) 10 hundred dollars = $1000 and \(C(101) =\)10.0499 hundred dollars = $1004.99, so it costs $4.99 for that 101st item. Using this definition, the marginal cost is $4.99.

- \( C'(x)=\frac{1}{2}x^{-1/2} = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{x}}\), so \( C'(100)=\frac{1}{2\sqrt{100}}=\frac{1}{20} \) hundred dollars = $5.00.

Note how close these answers are! This shows (again) why it’s OK that we use both definitions for marginal cost.

Demand is the functional relationship between the price \(p\) and the quantity \(q\) that can be sold (that is demanded). Depending on your situation, you might think of \(p\) as a function of \(q\), or of \(q\) as a function of \(p\)

Your revenue is the amount of money you actually take in from selling your products.

The Total Revenue (TR, or just R) for \(q\) items is the total amount of money you take in for selling \(q\) items. Total Revenue is price multiplied by quantity, \[TR = p \cdot q.\nonumber \]

The Average Revenue (AR) for \(q\) items is the total revenue divided by \(q\), or \[\frac{TR}{q}.\nonumber \]

The Marginal Revenue (MR) at \(q\) items is the revenue from producing the next item, \[MR(q) = TR(q + 1) - TR(q).\nonumber \]

Just as with marginal cost, we will use both this definition and the derivative definition: \[MR(q) = TR'(q).\nonumber \]

Your profit is what’s left over from total revenue after costs have been subtracted.

The Profit (P) for \(q\) items is \[TR(q) - TC(q),\nonumber \] the difference between total revenue and total costs.

The average profit for \(q\) items is \[\frac{P}{q}.\nonumber \]

The marginal profit at \(q\) items is \[P(q + 1) – P(q),\nonumber \] or \[P'(q)\nonumber \]

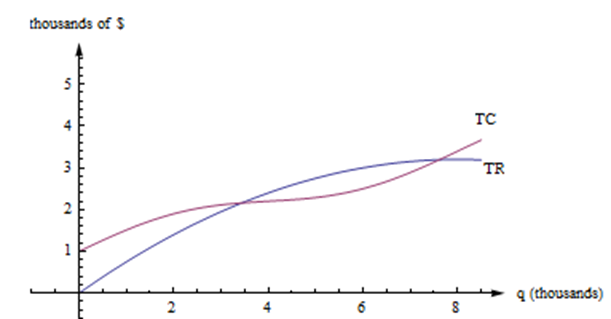

Graphical Interpretations of the Basic Business Math Terms

Illustration

Here are the graphs of TR and TC for producing and selling a certain item. The horizontal axis is the number of items, in thousands. The vertical axis is the number of dollars, also in thousands.

First, notice how to find the fixed cost and variable cost from the graph here. FC is the \(y\)-intercept of the TC graph. (\(FC = TC(0)\).) The graph of TVC would have the same shape as the graph of TC, shifted down. (\(TVC = TC - FC\).)

\(MC(q) = TC(q + 1) - TC(q)\), but that’s impossible to read on this graph. How could you distinguish between TC(4022) and TC(4023)? On this graph, that interval is too small to see, and our best guess at the secant line is actually the tangent line to the TC curve at that point. (This is the reason we want to have the derivative definition handy.)

\(MC(q)\) is the slope of the tangent line to the TC curve at \( (q, TC(q))\).

\(MR(q)\) is the slope of the tangent line to the TR curve at \((q, TR(q))\).

Profit is the distance between the TR and TC curve. If you experiment with a clear ruler, you’ll see that the biggest profit occurs exactly when the tangent lines to the TR and TC curves are parallel. This is the rule profit is maximized when \( MR = MC\)

which we'll explore later in the chapter.

The demand, \(D\), for a product at a price of \(p\) dollars is given by \( D(p)=200-0.2p^2 \). Find the marginal revenue when the price is $10.

Solution

First we need to form a revenue equation. Since Revenue = Price\( \times \)Quantity, and the demand equation shows the quantity of product that can be sold, we have \[R(p)=D(p)\cdot p=\left(200-0.2p^2\right)p=200p-0.2p^3.\nonumber \]

Now we can find marginal revenue by finding the derivative: \[R'(p)=200(1)-0.2(3p^2)=200-0.6p^2\nonumber \]

At a price of $10, \( R'(10)=200-0.6(10)^2=140 \).

Notice the units for \(R'\) are \(\frac{\text{dollars of Revenue}}{\text{dollar of price}}\), so \( R'(10)=140 \) means that when the price is $10, the revenue will increase by $140 for each dollar that the price was increased.