8.2: The Derivative

- Page ID

- 26567

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Definition of the Derivative

When working with linear functions, we could find the slope of a line to determine the rate at which the function is changing. For an arbitrary function, we can determine the average rate of change of the function. This is the slope of the secant line through those two points on the graph.

Average Rate of Change = \( \dfrac{\Delta \text{output}}{\Delta \text{input}} = \dfrac{f(b) - f(a)}{b-a}\)

= the slope of the secant line through the two points \(\left(a, f(a)\right)\) and \(\left(b, f(b)\right)\)

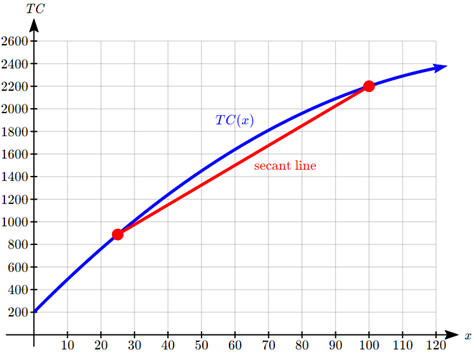

Suppose the total cost of producing \(x\) items is given by \(TC(x) = 200+30x-0.1x^2\). Determine the average rate of change of cost when increasing production from 25 units to 100 units.

Solution

The cost when producing 25 units is \(TC(25) = 200+30(25)-0.1(25)^2 = \$887.50\)

The cost when producing 100 units is \(TC(100) = 200+30(100)-0.1(100)^2 = \$2200\)

The cost increased by $2200-$887.50 = $1312.50 while production increased by 100 – 25 = 75 items. The average rate of change is:

\[\frac{TC(100) - TC(25)}{100 - 25} = \frac{2200-887.50}{100-25} = \frac{1312.50}{75} = 17.50 \text{ dollars per unit}\nonumber \]

This tells us that on average the cost increases by $17.50 for each unit produced.

The average rate of change is the slope of the secant line between (25, 887.50) and (100, 2200)

Thinking about the last example, suppose instead we asked the question "How fast are costs increasing when production is 25 units?" Notice this is a different kind of question. The question in the example asked for the rate of change over an interval, as production increased from one value to another. This question is again asking for a rate of change, but an instantaneous rate of change, at a particular moment.

We don’t yet have a way to calculated rate of change except over an interval. In the next example we will explore a couple ways to estimate the instantaneous rate of change.

Suppose the total cost of producing \(x\) items is given by \(TC(x) = 200+30x-0.1x^2\). Estimate the instantaneous rate of change when 25 items are being produced.

Solution

We can see in the previous graph that the secant slope on the interval \(25\leq x \leq 100\) is not a particularly good estimate of the instantaneous rate of change since the cost function seems steeper at \(x = 25\) then over the secant slope. We could improve the estimate by choosing a smaller interval.

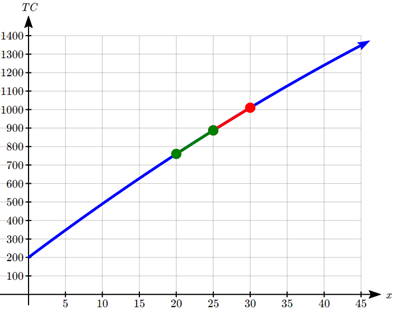

Approach 1: Using smaller intervals

Using the interval \(25\leq x \leq 30\), the average rate of change would be:

\[\frac{TC(30) - TC(25)}{30 - 25} = \frac{1010-887.50}{30-25} = \frac{122.50}{5} = 24.50 \text{ dollars per unit}\nonumber \]

Using an interval on the other side, \(20\leq x \leq 25\), the average rate of change would be:

\[\frac{TC(25) - TC(20)}{25 - 20} = \frac{887.50-760}{25-20} = \frac{127.5}{5} = 25.50 \text{ dollars per unit}\nonumber \]

Visually, we can see both these secant lines seem to approximate the function pretty well.

We would expect the instantaneous rate of change to be somewhere between these two values. Averaging them, we get an estimate of $25 per unit for the instantaneous rate of change.

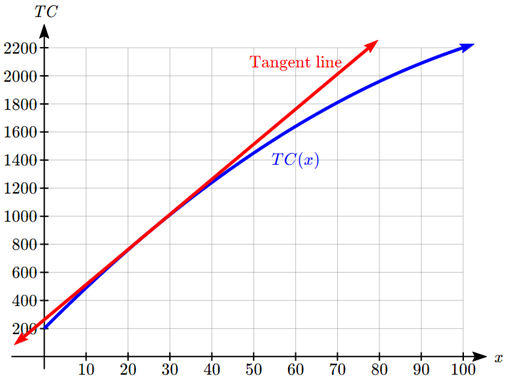

Approach 2: Estimating from the graph.

This approach is more commonly used when we only have the graph of a function, and don’t have a formula to evaluate, but we will illustrate it here using the same function.

The instantaneous rate of change is the slope of the tangent line, which is the line that just touches the graph at the point of interest, and has the same rate of change (slope) as the function does at the point. Given a graph, we can sketch in a tangent line by holding a ruler up to the graph, and drawing in a line that touches the graph when \(x = 25\) and has the same slope.

To estimate the instantaneous rate of change, we can now calculate the slope of this drawn-in line. Looking at the graph, the tangent line appears to pass approximately through (30, 1000) and (70, 2000) which would give a slope of \(\frac{2000-1000}{70-30}=\frac{1000}{40}=25\) dollars per unit.

Next we will explore the same ideas using a function defined in a table, and in another context.

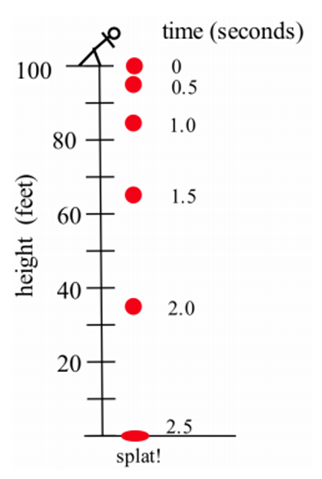

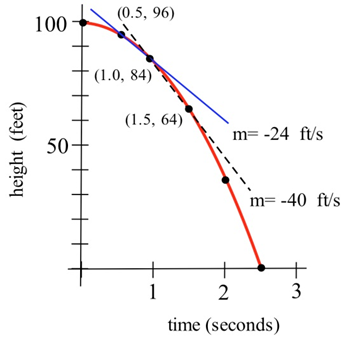

Suppose we drop a tomato from the top of a 100 foot building and time its fall.

|

Time (sec) |

Height (ft) |

|---|---|

|

0.0 |

100 |

|

0.5 |

96 |

|

1.0 |

84 |

|

1.5 |

64 |

|

2.0 |

36 |

|

2.5 |

0 |

- How long did it take for the tomato to drop 100 feet?

- How far did the tomato fall during the first second?

- How far did the tomato fall during the last second?

- How far did the tomato fall between \(t =0.5\) and \(t = 1\)?

- What was the average velocity of the tomato during its fall?

- What was the average velocity between \( t=1\) and \(t=2\) seconds?

- How fast was the tomato falling 1 second after it was dropped?

Solution

Some of these questions are pretty easy to answer, while some are more complex.

- From the table, it took 2.5 seconds for the tomato to drop 100 feet

- During the first second, the tomato fell 100 – 84 = 16 feet

- During the last second, the tomato fell 64 – 0 = 64 feet

- Between \(t =0.5\) and \(t = 1\) the tomato fell 96 – 84 = 12 feet

- Velocity is similar to speed, and is a rate of change. We can calculate average velocity the same way we did average rate of change earlier.

\[\text{Average velocity}=\frac{\text{distance fallen}}{\text{total time}}=\frac{\Delta\text{position}}{\Delta\text{time}}=\frac{-100 \text{ ft}}{2.5 \text{ s}}=-40 \text{ ft/s}\nonumber \] - Between \( t=1\) and \(t=2\) seconds, \[\text{Average velocity}=\frac{\Delta\text{position}}{\Delta\text{time}}=\frac{36\text{ ft}- 84\text{ ft}}{2\text{ s} - 1\text{ s}}=\frac{-48 \text{ ft}}{1 \text{ s}}=-48 \text{ ft/s}\nonumber \]

- This question is significantly different from the previous two questions about average velocity. Here we want the instantaneous velocity, the velocity at an instant in time. Unfortunately the tomato is not equipped with a speedometer so we will have to give an approximate answer. Like in our Approach 1 in the previous example, we will estimate it using secant slopes.

One crude approximation of the instantaneous velocity after 1 second is simply the average velocity during the entire fall, -40 ft/s. But the tomato fell slowly at the beginning and rapidly near the end so the "-40 ft/s" estimate may or may not be a good answer.

We can get a better approximation of the instantaneous velocity at \(t=1\) by calculating the average velocities over a short time interval near \(t = 1\). The average velocity between \(t = 0.5\) and \(t = 1\) is \(\dfrac{-12\text{ feet}}{0.5\text{ s}} = -24\text{ ft/s}\), and the average velocity between \(t = 1\) and \(t = 1.5\) is \(\dfrac{-20\text{ feet}}{0.5\text{ s}} = -40\text{ ft/s}\) so we can be reasonably sure that the instantaneous velocity is between -24 ft/s and -40 ft/s. The average, –32 ft/s, would be a good estimate for the instantaneous velocity.

In general, the shorter the time interval over which we calculate the average velocity, the better the average velocity will approximate the instantaneous velocity.

The average velocity over a time interval is \( \dfrac{\Delta\text{position}}{\Delta\text{time}} \), which is the slope of the secant line through two points on the graph of height versus time. The instantaneous velocity at a particular time and height is the slope of the tangent line to the graph at the point given by that time and height.

Average velocity = \( \dfrac{\Delta\text{position}}{\Delta\text{time}} \) = slope of the secant line through 2 points.

Instantaneous velocity = slope of the line tangent to the graph.

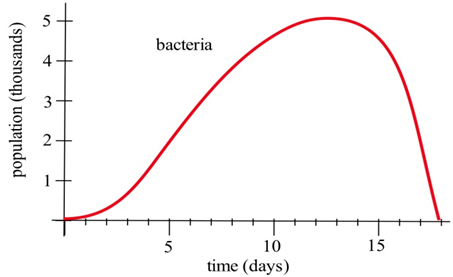

Suppose we set up a machine to count the number of bacteria growing on a Petri plate. At first there are few bacteria so the population grows slowly. Then there are more bacteria to divide so the population grows more quickly. Later, there are more bacteria and less room and nutrients available for the expanding population, so the population grows slowly again. Finally, the bacteria have used up most of the nutrients, and the population declines as bacteria die.

Use the population graph to estimate the answer to the questions below.

- What is the bacteria population at time \(t = 3\) days?

- What is the population increment from \(t = 3\) to \(t =10\) days?

- What is the rate of population growth from \(t = 3\) to \(t = 10\) days?

- What is the rate of population growth on the third day, at \(t = 3\) ?

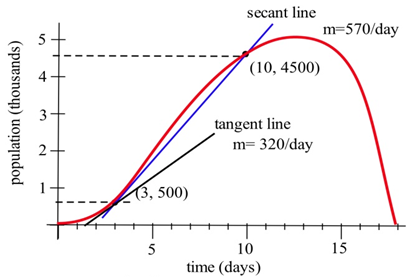

Solution

- From the graph, at \(t = 3\), the population is about 0.5 thousand, or 500 bacteria.

- At \(t = 10\), the population is about 4.5 thousand, so the increment is about 4000 bacteria.

- The rate of growth from \(t = 3\) to \(t = 10\) is the average rate of change in population during that time: \[ \begin{align*} \text{average change in population } & = \frac{\text{change in population}}{\text{change in time}}\\ & = \frac{\Delta\text{population}}{\Delta\text{time}} \\ & = \frac{4000\text{ bacteria}}{7\text{ days}} \\ & \approx 570\text{ bacteria/day}. \end{align*} \nonumber \]

This is the slope of the secant line through the two points (3, 500) and (10, 4500).

- This question is asking for the instantaneous rate of population change, the slope of the line which is tangent to the population curve at (3, 500). If we sketch a line approximately tangent to the curve at (3, 500) and pick two points near the ends of the tangent line segment, we can estimate that instantaneous rate of population growth is approximately 320 bacteria/day.

In the previous examples, we noticed that as the interval got smaller and smaller, the secant line got closer to the tangent line and its slope got closer to the slope of the tangent line. That’s good news – we know how to find the slope of a secant line.

Let's explore further this idea of finding the tangent slope based on the secant slope.

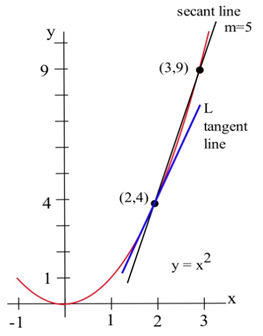

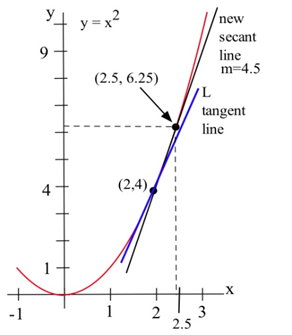

Find the slope of the line \(L\) in the graph below which is tangent to \(f(x) = x^2\) at the point (2,4).

We could estimate the slope of \(L\) from the graph, but we won't. Instead, we will use the idea that secant lines over tiny intervals approximate the tangent line.

We can see that the line through (2,4) and (3,9) on the graph of \(f\) is an approximation of the slope of the tangent line, and we can calculate that slope exactly: \(m = \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} = \frac{9-4}{3-2} = 5\). But \(m = 5\) is only an estimate of the slope of the tangent line and not a very good estimate. It's too big. We can get a better estimate by picking a second point on the graph of \(f\) which is closer to (2,4). The point (2,4) is fixed and it must be one of the points we use.

From the second figure, we can see that the slope of the line through the points (2,4) and (2.5,6.25) is a better approximation of the slope of the tangent line at (2,4): \(m = \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} = \frac{6.25 - 4}{2.5 - 2} = \frac{2.25}{0.5} = 4.5 \), a better estimate, but still an approximation. We can continue picking points closer and closer to (2,4) on the graph of \(f\), and then calculating the slopes of the lines through each of these points and the point (2,4):

| \( x \) | \( y=x^2 \) | Slope of line through \( (x,y) \) and (2,4). |

| 1.5 | 2.25 | 3.5 |

| 1.9 | 3.61 | 3.9 |

| 1.99 | 3.9601 | 3.99 |

| \( x \) | \( y=x^2 \) | Slope of line through \( (x,y) \) and (2,4). |

| 3 | 9 | 5 |

| 2.5 | 6.25 | 4.5 |

| 2.01 | 4.0401 | 4.01 |

The only thing special about the \(x\)–values we picked is that they are numbers which are close, and very close, to \(x = 2\). Someone else might have picked other nearby values for \(x\). As the points we pick get closer and closer to the point (2,4) on the graph of \( y = x^2\), the slopes of the lines through the points and (2,4) are better approximations of the slope of the tangent line, and these slopes are getting closer and closer to 4.

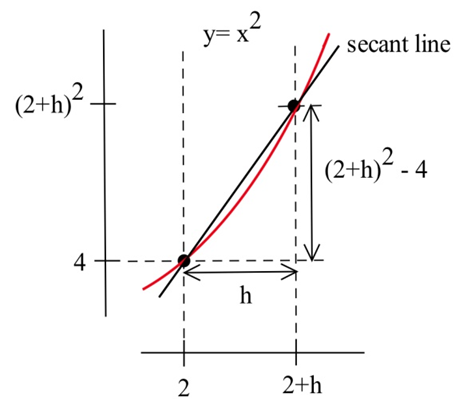

We can bypass much of the calculating by not picking the points one at a time: let's look at a general point near (2,4). Define \( x = 2 + h\) so \(h\) is the increment from 2 to \(x\). If \(h\) is small, then \(x = 2 + h\) is close to 2 and the point \((2+h, f(2+h) ) = \left(2+h, (2+h)^2\right) \) is close to (2,4). The slope \(m\) of the line through the points (2,4) and \(\left(2+h, (2+h)^2\right)\) is a good approximation of the slope of the tangent line at the point (2,4):

We can calculate the secant slope for any value of \(h\):

\[ m = \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} = \frac{(2+h)^2-4}{(2+h)-2} = \frac{\left(4+4h+h^2\right)-4}{h} = \frac{4h+h^2}{h} = \frac{h(4+h)}{h} = 4+h \nonumber\]

The value \( m = 4 + h \) is the slope of the secant line through the two points (2,4) and \(\left( 2+h, (2+h)^2 \right)\). As \(h\) gets smaller and smaller, this slope approaches the slope of the tangent line to the graph of \(f\) at (2,4).

More formally, we could write: \[\text{Slope of the tangent line} = \lim\limits_{h\to 0} \dfrac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} = \lim\limits_{h\to 0} (4+h). \nonumber \]

We can easily evaluate this limit using direct substitution, finding that as the interval \(h\) shrinks towards 0, the secant slope approaches the tangent slope, 4.

Use the applet below to explore this. You can drag the base point on the graph to explore the behavior at different locations on the graph. Once setting the base point, use the slider to see how the secant lines approach the tangent line as \(h\) approaches zero.

Finding tangent slopes and finding the instantaneous rate of change are the same problem. In each problem we wanted to know how rapidly something was changing at an instant in time, and the answer turned out to be finding the slope of a tangent line, which we approximated with the slope of a secant line. This idea is the key to defining the slope of a curve.

We can view the derivative in different ways. Here are a three of them:

- The derivative of a function \(f\) at a point \((x, f(x))\) is the instantaneous rate of change.

- The derivative is the slope of the tangent line to the graph of \(f\) at the point \((x, f(x))\).

- The derivative is the slope of the curve \(f(x)\) at the point \((x, f(x))\).

A function is called differentiable at \((x, f(x))\) if its derivative exists at \((x, f(x))\).

Notation for the Derivative

The derivative of \(y = f(x)\) with respect to \(x\) is written as \[f'(x)\nonumber \] (read aloud as "\(f\) prime of \(x\)"), or \[y'\nonumber \] (read aloud as "why prime") or \[\frac{dy}{dx}\nonumber \] (read aloud as "dee why dee ex"), or \[\frac{df}{dx}.\nonumber \]

The notation that resembles a fraction is called Leibniz notation. It displays not only the name of the function (\(f\) or \(y\)), but also the name of the variable (in this case, \(x\)). It looks like a fraction because the derivative is a slope. In fact, this is simply \( \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} \) written in Roman letters instead of Greek letters.

Verb Forms

We find the derivative of a function, or take the derivative of a function, or differentiate a function.

We use an adaptation of the \( \frac{df}{dx} \) notation to mean "find the derivative of \(f(x)\):" \[\frac{d}{dx}\left[f(x)\right]=\frac{df}{dx}.\nonumber \] [The book uses parentheses instead of brackets–both are acceptable forms of the notation.]

Formal Algebraic Definition

\[f'(x)=\lim\limits_{h\to 0} \dfrac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}\nonumber \]

Practical Definition

The derivative can be approximated by looking at an average rate of change, or the slope of a secant line, over a very tiny interval. The tinier the interval, the closer this is to the true instantaneous rate of change, slope of the tangent line, or slope of the curve.

Looking Ahead

We will have methods for computing exact values of derivatives from formulas soon. If the function is given to you as a table or graph, you will still need to approximate this way.

This is the foundation for the rest of this chapter. It’s remarkable that such a simple idea (the slope of a tangent line) and such a simple definition (for the derivative \( f'(x) \)) will lead to so many important ideas and applications.

Find the slope of the tangent line to \( f(x)=\frac{1}{x} \) at \(x = 3\).

Solution

The slope of the tangent line is the value of the derivative \(f'(3)\). \( f(3)=\frac{1}{3}\) and \( f(3+h)=\frac{1}{3+h} \), so, using the formal limit definition of the derivative, \[ f'(3)=\lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{f(3+h)-f(3)}{h}=\lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{\frac{1}{3+h}-\frac{1}{3}}{h}. \nonumber \]

We can simplify by giving the fractions a common denominator: \[ \begin{align*} \lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{\frac{1}{3+h}-\frac{1}{3}}{h} & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{\frac{1}{3+h}\cdot\frac{3}{3}-\frac{1}{3}\cdot\frac{3+h}{3+h}}{h} \\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{\frac{3}{9+3h}-\frac{3+h}{9+3h}}{h} \\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{\frac{3-(3+h)}{9+3h}}{h} \\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{\frac{3-3-h}{9+3h}}{h} \\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{\frac{-h}{9+3h}}{h} \\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{-h}{9+3h}\cdot\frac{1}{h} \\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{-1}{9+3h} \\ \end{align*} \] and the evaluate using direct substitution: \[\lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{-1}{9+3h}=\frac{-1}{9+3(0)}=-\frac{1}{9}.\nonumber \]

Thus, the slope of the tangent line to \( f(x)=\frac{1}{x} \) at \(x = 3\) is \( -\frac{1}{9} \).

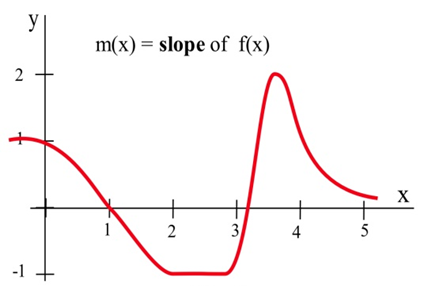

The Derivative as a Function

We now know how to find (or at least approximate) the derivative of a function for any \(x\)-value; this means we can think of the derivative as a function, too. The inputs are the same \(x\)’s; the output is the value of the derivative at that \(x\) value.

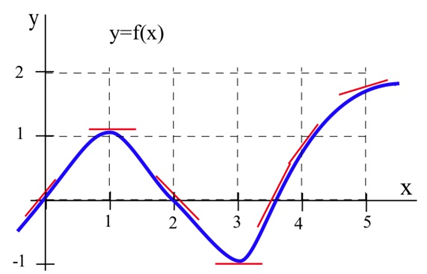

Below is the graph of a function \( y=f(x) \). We can use the information in the graph to fill in a table showing values of \( f'(x): \)

At various values of \(x\), draw your best guess at the tangent line and measure its slope. You might have to extend your lines so you can read some points. In general, your estimate of the slope will be better if you choose points that are easy to read and far away from each other. Here are estimates for a few values of \(x\) (parts of the tangent lines used are shown above in the graph):

| \( x \) | \( y=f(x) \) | \( f'(x)= \) the estimated slope of the tangent line to the curve at the point \( (x,y) \). |

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | -1 |

| 3 | -1 | 0 |

| 3.5 | 0 | 2 |

We can estimate the values of \(f'(x)\) at some non-integer values of \(x\), too: \(f'(0.5) \approx 0.5\) and \(f'(1.3) \approx -0.3\).

We can even think about entire intervals. For example, if \(0 \lt x \lt 1\), then \(f(x)\) is increasing, all the slopes are positive, and so \(f'(x)\) is positive.

The values of \(f'(x)\) definitely depend on the values of \(x\), and \(f'(x)\) is a function of \(x\). We can use the results in the table to help sketch the graph of \(f'(x)\).

To get a better feel for this, explore the applet below. The top graph is the graph of the original function \(g(x)\). The bottom graph shows the slopes of \(g(x)\), so is a graph of the derivative, \(g'(x)\). Drag the point a and notice how the slope of the tangent line corresponds to the value of the derivative \(g'(x)\).

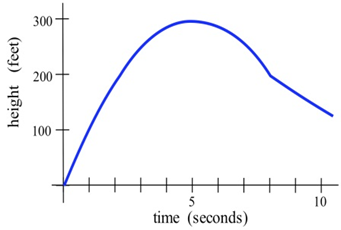

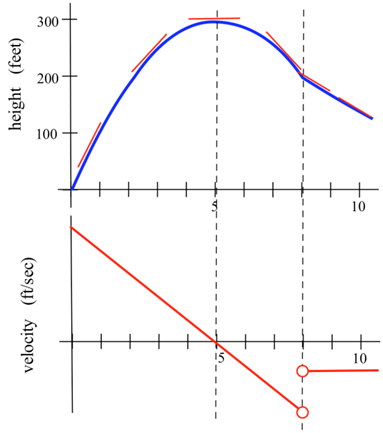

Shown is the graph of the height \(h(t)\) of a rocket at time \(t\).

Sketch the graph of the velocity of the rocket at time \(t\). (Velocity is the derivative of the height function, so it is the slope of the tangent to the graph of position or height.)

We can estimate the slope of the function at several points. The lower graph below shows the velocity of the rocket. This is \(v(t) = h'(t)\).

In some applications, we need to know where the graph of a function \(f(x)\) has horizontal tangent lines (slopes = 0).

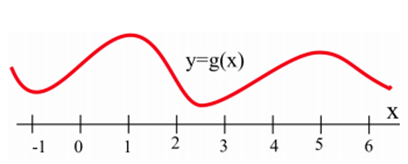

Below is the graph of \(y = g(x)\). At what values of \(x\) does the graph of \(g(x)\) have horizontal tangent lines?

The tangent lines to the graph of \(g(x)\) are horizontal (slope = 0) when \(x\approx -1, 1, 2.5, \text{ and } 5\).

We can also find derivative functions algebraically using limits.

Find \( \frac{d}{dx}\left( 2x^2-4x-1 \right) \).

Setting up the derivative using a limit, \[ f'(x)=\lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}.\nonumber \]

We will start by simplifying \( f(x+h) \) by expanding: \[ \begin{align*} f(x+h) & = 2(x+h)^2-4(x+h)-1 \\ & = 2(x^2+2xh+h^2)-4(x+h)-1 \\ & = 2x^2+4xh+2h^2-4x-4h-1 \end{align*} \nonumber \]

Now finding the limit: \[ \begin{align*} f'(x) & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h} \\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0} \frac{(2x^2+4xh+2h^2-4x-4h-1)-(2x^2-4x-1)}{h} \\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0} \frac{2x^2+4xh+2h^2-4x-4h-1-2x^2+4x+1}{h} \qquad \text{(Substitute in the formulas.)} \\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0} \frac{4xh+2h^2-4h}{h} \qquad \text{(Now simplify.)}\\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0} \frac{h(4x+2h-4)}{h} \qquad \text{(Factor out the \( h \), then cancel.)} \\ & = \lim\limits_{h\to 0} (4x+2h-4) \end{align*} \nonumber \] We can find the limit of this expression by direct substitution: \[ f'(x)=\lim\limits_{h\to 0} (4x+2h-4)=4x-4\nonumber \]

Notice that the derivative depends on \(x\), and that this formula will tell us the slope of the tangent line to \(f\) at any value \(x\). For example, if we wanted to know the tangent slope of \(f\) at \(x = 3\), we would simply evaluate: \( f'(3)=4(3)-4=8 \).

A formula for the derivative function is very powerful, but as you can see, calculating the derivative using the limit definition is very time consuming. In the next section, we will identify some patterns that will allow us to start building a set of rules for finding derivatives without needing the limit definition.

Interpreting the Derivative

So far we have emphasized the derivative as the slope of the line tangent to a graph. That interpretation is very visual and useful when examining the graph of a function, and we will continue to use it. Derivatives, however, are used in a wide variety of fields and applications, and some of these fields use other interpretations. The following are a few interpretations of the derivative that are commonly used.

General

Rate of Change: \(f '(x)\) is the rate of change of the function at \(x\). If the units for \(x\) are years and the units for \(f(x)\) are people, then the units for \( \frac{df}{dx} \) are \(\frac{\text{people}}{\text{year}}\), a rate of change in population.

Graphical

Slope: \(f '(x)\) is the slope of the line tangent to the graph of \(f\) at the point \(( x, f(x) )\).

Physical

Velocity: If \(f(x)\) is the position of an object at time \(x\), then \(f '(x)\) is the velocity of the object at time \(x\). If the units for \(x\) are hours and \(f(x)\) is distance measured in miles, then the units for \(\mathbf{f '}(x) = \frac{df}{dx}\) are \( \frac{\text{miles}}{\text{hour}} \), miles per hour, which is a measure of velocity.

Acceleration: If \(f(x)\) is the velocity of an object at time \(x\), then \(f '(x)\) is the acceleration of the object at time \(x\). If the units are for \(x\) are hours and \(f(x)\) has the units \( \frac{\text{miles}}{\text{hour}} \), then the units for the acceleration \(\mathbf{f '(x)} = \frac{df}{dx}\) are \( \frac{\text{miles/hour}}{\text{hour}} =\frac{\text{miles}}{\text{hour}^2} \), miles per hour per hour.

Business

Marginal Cost, Marginal Revenue, and Marginal Profit: We'll explore these terms in more depth later in the section. Basically, the marginal cost is approximately the additional cost of making one more object once we have already made \(x\) objects. If the units for \(x\) are bicycles and the units for \(f(x)\) are dollars, then the units for \(f '(x) = \frac{df}{dx}\) are \( \frac{\text{ dollars}}{\text{ bicycle}} \), the cost per bicycle.

In business contexts, the word "marginal" usually means the derivative or rate of change of some quantity.

One of the strengths of calculus is that it provides a unity and economy of ideas among diverse applications. The vocabulary and problems may be different, but the ideas and even the notations of calculus are still useful.

Suppose the demand curve for widgets was given by \( D(p)=\frac{1}{p} \), where \(D\) is the quantity of widgets, in thousands, at a price of \(p\) dollars. Interpret the derivative of \(D\) at \(p = \)$3.

Note that we calculated \( D'(3) \) earlier to be \( D'(3)=-\frac{1}{9}\approx -0.111 \).

Since \(D\) has units thousands of widgets

and the units for \(p\) is dollars of price, the units for \(D'\) will be \( \frac{\text{thousands of widgets}}{\text{dollar of price}} \). In other words, it shows how the demand will change as the price increases.

Specifically, \( D'(3)\approx -0.111 \) tells us that when the price is $3, the demand will decrease by about 0.111 thousand items for every dollar the price increases.

(Note: The screen shots in the following video are from an earlier version of the book, so some of the section numbers or titles may not look the same. However, much of the content is the same, and the comments still apply.)