3.5: Graphs and Properties of Logarithmic Functions

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

In this section, you will:

- examine properties of logarithmic functions

- examine graphs of logarithmic functions

- examine the relationship between graphs of exponential and logarithmic functions

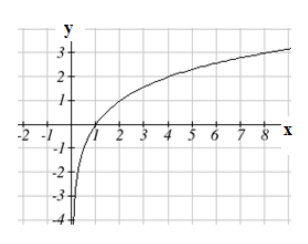

Recall that the exponential function f(x)=2x produces this table of values

| x | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| f(x) | 1/8 | 1/4 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 |

Since the logarithmic function is an inverse of the exponential, g(x)=log2(x) produces the table of values

| x | 1/8 | 1/4 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 |

| g(x) | -3 | -2 | -1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

In this second table, notice that

- As the input increases, the output increases.

- As input increases, the output increases more slowly.

- Since the exponential function only outputs positive values, the logarithm can only accept positive values as inputs, so the domain of the log function is (0,∞).

- Since the exponential function can accept all real numbers as inputs, the logarithm can have any real number as output, so the range is all real numbers or (−∞,∞).

Plotting the graph of g(x)=log2(x) from the points in the table , notice that as the input values for x approach zero, the output of the function grows very large in the negative direction, indicating a vertical asymptote at x=0.

In symbolic notation we write

as x→0+, f(x)→−∞

and as x→∞,f(x)→∞

Source: The material in this section of the textbook originates from David Lippman and Melonie Rasmussen, Open Text Bookstore, Precalculus: An Investigation of Functions, “Chapter 4: Exponential and Logarithmic Functions,” licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0 license. The material here is based on material contained in that textbook but has been modified by Roberta Bloom, as permitted under this license.

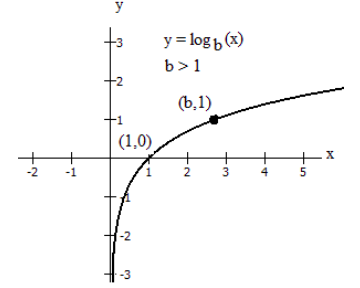

Graphically, in the function g(x)=logb(x), b>1, we observe the following properties:

- The graph has a horizontal intercept at (1, 0)

- The line x = 0 (the y-axis) is a vertical asymptote; as x→0+,y→−∞

- The graph is increasing if b>1

- The domain of the function is x>0, or (0, ∞)

- The range of the function is all real numbers, or (−∞,∞)

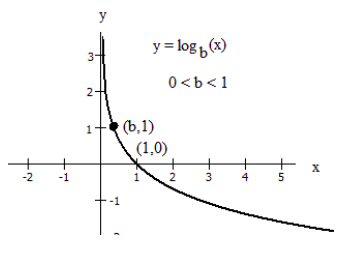

However if the base b is less than 1, 0 < b < 1, then the graph appears as below.

This follows from the log property of reciprocal bases : log1/bC=−logb(C)

- The graph has a horizontal intercept at (1, 0)

- The line x = 0 (the y-axis) is a vertical asymptote; as x→0+,y→∞

- The graph is decreasing if 0 < b < 1

- The domain of the function is x > 0, or (0, ∞)

- The range of the function is all real numbers, or (−∞,∞)

When graphing a logarithmic function, it can be helpful to remember that the graph will pass through the points (1, 0) and (b, 1).

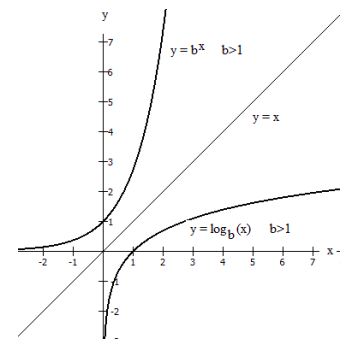

Finally, we compare the graphs of y=bx and y=logb(x), shown below on the same axes.

Because the functions are inverse functions of each other, for every specific ordered pair

(h, k) on the graph of y=bx, we find the point (k, h) with the coordinates reversed on the graph of y=logb(x).

In other words, if the point with x=h and y=k is on the graph of y=bx, then the point with x=k and y=h lies on the graph of y=logb(x)

The domain of y=bx is the range of y=logb(x)

The range of y=bx is the domain of y=logb(x)

For this reason, the graphs appear as reflections, or mirror images, of each other across the diagonal line y=x. This is a property of graphs of inverse functions that students should recall from their study of inverse functions in their prerequisite algebra class.

| y=bx, with b>1 | y=logb(x), with b>1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Domain | 1}\)" valign="top" width="188" class="lt-math-38599">

all real numbers |

1}\)" valign="top" width="189" class="lt-math-38599">

all positive real numbers |

| Range | 1}\)" valign="top" width="188" class="lt-math-38599">

all positive real numbers |

1}\)" valign="top" width="189" class="lt-math-38599">

all real numbers |

| Intercepts | 1}\)" valign="top" width="188" class="lt-math-38599">

(0,1) |

1}\)" valign="top" width="189" class="lt-math-38599">

(1,0) |

| Asymptotes | 1}\)" valign="top" width="188" class="lt-math-38599">

Horizontal asymptote is As x→−∞,y→0 |

1}\)" valign="top" width="189" class="lt-math-38599">

Vertical asymptote is As x→0+,y→−∞ |

Source: The material in this section of the textbook originates from David Lippman and Melonie Rasmussen, Open Text Bookstore, Precalculus: An Investigation of Functions, “Chapter 4: Exponential and Logarithmic Functions,” licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0 license. The material here is based on material contained in that textbook but has been modified by Roberta Bloom, as permitted under this license.