3.2: What is Central Tendency

- Page ID

- 2090

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Identify situations in which knowing the center of a distribution would be valuable

- Give three different ways the center of a distribution can be defined

- Describe how the balance is different for symmetric distributions than it is for asymmetric distributions

What is "central tendency," and why do we want to know the central tendency of a group of scores? Let us first try to answer these questions intuitively. Then we will proceed to a more formal discussion.

Imagine this situation: You are in a class with just four other students, and the five of you took a \(5\)-point pop quiz. Today your instructor is walking around the room, handing back the quizzes. She stops at your desk and hands you your paper. Written in bold black ink on the front is "\(3/5\)." How do you react? Are you happy with your score of \(3\) or disappointed? How do you decide? You might calculate your percentage correct, realize it is \(60\%\), and be appalled. But it is more likely that when deciding how to react to your performance, you will want additional information. What additional information would you like?

If you are like most students, you will immediately ask your neighbors, "Whad'ja get?" and then ask the instructor, "How did the class do?" In other words, the additional information you want is how your quiz score compares to other students' scores. You therefore understand the importance of comparing your score to the class distribution of scores. Should your score of \(3\) turn out to be among the higher scores, then you'll be pleased after all. On the other hand, if \(3\) is among the lower scores in the class, you won't be quite so happy.

This idea of comparing individual scores to a distribution of scores is fundamental to statistics. So let's explore it further, using the same example (the pop quiz you took with your four classmates). Three possible outcomes are shown in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\). They are labeled "\(\text{Dataset A}\)," "\(\text{Dataset B}\)," and "\(\text{Dataset C}\)." Which of the three datasets would make you happiest? In other words, in comparing your score with your fellow students' scores, in which dataset would your score of \(3\) be the most impressive?

In \(\text{Dataset A}\), everyone's score is \(3\). This puts your score at the exact center of the distribution. You can draw satisfaction from the fact that you did as well as everyone else. But of course it cuts both ways: everyone else did just as well as you.

| Student | Dataset A | Dataset B | Dataset C |

|---|---|---|---|

| You | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| John's | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Maria's | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Shareecia's | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Luther's | 3 | 5 | 1 |

Now consider the possibility that the scores are described as in \(\text{Dataset B}\). This is a depressing outcome even though your score is no different than the one in \(\text{Dataset A}\). The problem is that the other four students had higher grades, putting yours below the center of the distribution.

Finally, let's look at \(\text{Dataset C}\). This is more like it! All of your classmates score lower than you so your score is above the center of the distribution.

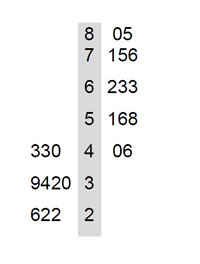

Now let's change the example in order to develop more insight into the center of a distribution. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows the results of an experiment on memory for chess positions. Subjects were shown a chess position and then asked to reconstruct it on an empty chess board. The number of pieces correctly placed was recorded. This was repeated for two more chess positions. The scores represent the total number of chess pieces correctly placed for the three chess positions. The maximum possible score was \(89\).

Two groups are compared. On the left are people who don't play chess. On the right are people who play a great deal (tournament players). It is clear that the location of the center of the distribution for the non-players is much lower than the center of the distribution for the tournament players.

We're sure you get the idea now about the center of a distribution. It is time to move beyond intuition. We need a formal definition of the center of a distribution. In fact, we'll offer you three definitions! This is not just generosity on our part. There turn out to be (at least) three different ways of thinking about the center of a distribution, all of them useful in various contexts. In the remainder of this section we attempt to communicate the idea behind each concept. In the succeeding sections we will give statistical measures for these concepts of central tendency.

Definitions of Center

Now we explain the three different ways of defining the center of a distribution. All three are called measures of central tendency.

Balance Scale

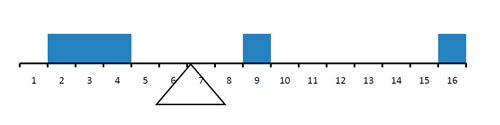

One definition of central tendency is the point at which the distribution is in balance. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows the distribution of the five numbers \(2, 3, 4, 9, 16\) placed upon a balance scale. If each number weighs one pound, and is placed at its position along the number line, then it would be possible to balance them by placing a fulcrum at \(6.8\).

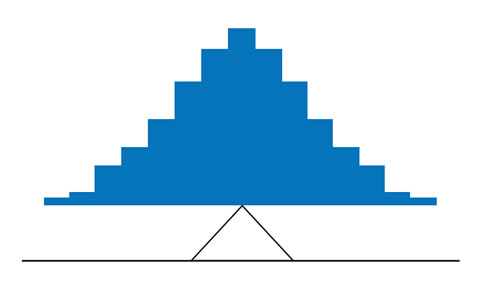

For another example, consider the distribution shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). It is balanced by placing the fulcrum in the geometric middle.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) illustrates that the same distribution can't be balanced by placing the fulcrum to the left of center.

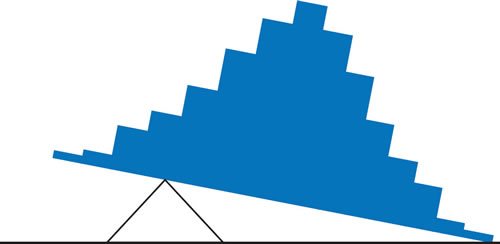

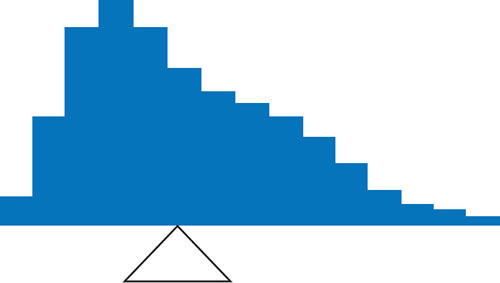

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) shows an asymmetric distribution. To balance it, we cannot put the fulcrum halfway between the lowest and highest values (as we did in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Placing the fulcrum at the "half way" point would cause it to tip towards the left.

The balance point defines one sense of a distribution's center. The simulation in the next section "Balance Scale Simulation" shows how to find the point at which the distribution balances.

Smallest Absolute Deviation

Another way to define the center of a distribution is based on the concept of the sum of the absolute deviations (differences). Consider the distribution made up of the five numbers \(2, 3, 4, 9, 16\). Let's see how far the distribution is from \(10\) (picking a number arbitrarily). Table \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows the sum of the absolute deviations of these numbers from the number \(10\).

| Values | Absolute Deviations from 10 |

|---|---|

| 2 | 8 |

| 3 | 7 |

| 4 | 6 |

| 9 | 1 |

| 16 | 6 |

| Sum | 28 |

The first row of the table shows that the absolute value of the difference between \(2\) and \(10\) is \(8\); the second row shows that the absolute difference between \(3\) and \(10\) is \(7\), and similarly for the other rows. When we add up the five absolute deviations, we get \(28\). So, the sum of the absolute deviations from \(10\) is \(28\). Likewise, the sum of the absolute deviations from \(5\) equals \(3 + 2 + 1 + 4 + 11 = 21\). So, the sum of the absolute deviations from \(5\) is smaller than the sum of the absolute deviations from \(10\). In this sense, \(5\) is closer, overall, to the other numbers than is \(10\).

We are now in a position to define a second measure of central tendency, this time in terms of absolute deviations. Specifically, according to our second definition, the center of a distribution is the number for which the sum of the absolute deviations is smallest. As we just saw, the sum of the absolute deviations from \(10\) is \(28\) and the sum of the absolute deviations from \(5\) is \(21\). Is there a value for which the sum of the absolute deviations is even smaller than \(21\)? Yes. For these data, there is a value for which the sum of absolute deviations is only \(20\). See if you can find it. A general method for finding the center of a distribution in the sense of absolute deviations is provided in the simulation "Absolute Differences Simulation."

Smallest Squared Deviation

We shall discuss one more way to define the center of a distribution. It is based on the concept of the sum of squared deviations (differences). Again, consider the distribution of the five numbers \(2, 3, 4, 9, 16\). Table \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows the sum of the squared deviations of these numbers from the number \(10\).

| Values | Squared Deviations from 10 |

|---|---|

| 2 | 64 |

| 3 | 49 |

| 4 | 36 |

| 9 | 1 |

| 16 | 36 |

| Sum | 186 |

The first row in the table shows that the squared value of the difference between \(2\) and \(10\) is \(64\); the second row shows that the squared difference between \(3\) and \(10\) is \(49\), and so forth. When we add up all these squared deviations, we get \(186\). Changing the target from \(10\) to \(5\), we calculate the sum of the squared deviations from \(5\) as \(9 + 4 + 1 + 16 + 121 = 151\). So, the sum of the squared deviations from \(5\) is smaller than the sum of the squared deviations from \(10\). Is there a value for which the sum of the squared deviations is even smaller than \(151\)? Yes, it is possible to reach \(134.8\). Can you find the target number for which the sum of squared deviations is \(134.8\)?

The target that minimizes the sum of squared deviations provides another useful definition of central tendency (the last one to be discussed in this section). It can be challenging to find the value that minimizes this sum. You will see how you do it in the upcoming section "Squared Differences Simulation."

Contributor

Online Statistics Education: A Multimedia Course of Study (http://onlinestatbook.com/). Project Leader: David M. Lane, Rice University.

- David M. Lane and Heidi Ziemer