5.4: Clinical trials

- Page ID

- 45051

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

Two areas of inquiry have contributed enormously to our understanding of experimental design: agriculture research and human subject clinical trials. This page outlines types of clinical trial designs and briefly introduces the subject of research ethics with respect to human subject research.

An outline of clinical trials

Much has been written about biomedical research study design; a couple of accessible articles that can supplement the material presented here include Benson and Hart 2000, Concato et al 2000, Gabriella 2012. Even if you never work in clinical research, understanding how clinical trials are designed and under what circumstances limitations of particular designs arise is helpful to all of us who do experimental work. In Mike’s Workbook for Biostatistics we will present descriptions of research activities and step through situations where you will attempt to align the research by analogy to clinical trials. A second approach to learning about experimental design is to read about someone’s study, and reworking it in terms of a clinical trial design perspective. We will use a discussion of clinical trials, used in biomedical research to investigate effectiveness of treatments of disease, as our starting point for learning how statistics informs experimentation.

Types of clinical trials are distinguished by their design and include:

Experimental studies are just that, research designs that apply techniques of experimental science — controls, randomization, attempts to account for sources of bias. They are intended to make direct comparisons among subjects assigned by the researcher to treatment groups. By definition experiments are longitudinal studies. Longitudinal studies are experimental or observational studies in which multiple observations are recorded for each individual and individuals are tracked over time. Many excellent resources about experimental design are available, from R.A. Fisher’s 1935 book, The design of experiments, to Scheiner and Gurevitch (Editors) 2001, Design and Analysis of Ecological Experiments (2nd edition), to the many books on randomized control trials, e.g., the 5th edition of Designing clinical research (2022), edited by Browner et al.

Observational (or epidemiological) studies — no direct intervention is administered and so observational studies tend to be retrospective; we identify individuals with and without the condition and attempt to identify associations between the condition and any number of potential causal factors.

Cross-sectional studies are examples of descriptive study designs. They take observations at one point in time on a variety of individuals. It can be used to associate factors with the condition in question, and can be used to estimate the prevalence of a condition in the population. Cross-sectional studies are referred to as method = cross.sectional in the package epiR. Omair (2015) provides an accessible summary of case and cross-sectional study designs.

Cohort studies involve a group of subjects (e.g., patients) who receive the same treatment at the same time. Cohort studies are referred to as method = cohort.count in the package epiR. A cohort consists of subjects who are linked in some way. It could be a trivial link, like the cohorting done at university (all incoming Freshmen students who enroll for a class offered at 9:30 AM), or it could be based on shared experience due to an exposure event (e.g., all passengers on a jet traveling with an index case or “patient zero”).

- Prospective cohort studies enroll people as cohorts at the beginning of a study and follow them over time.

- Retrospective cohort studies may utilize archived records.

Cohort and other variations of observational studies (e.g., case control) can establish associations between risk factors and conditions or specific adverse events, but cannot by themselves establish cause and effect (Benson and Hartz 2000).

Case control studies are similar to cohort studies, except they are retrospective. Case refers to subjects with one or more characteristics of interest. Used to infer the exposure risk factor by evaluating historical records. Case control studies are referred to as method = case.control in the package epiR. Omair (2016) provides an accessible summary of cohort and case control study designs. Designed to identify associations between exposure and particular outcomes, case control studies are retrospective and observational studies: retrospective because the outcomes are already known, and observational because the event was caused by nature, not experiment. In principle, researchers identify a number of cases with a particular outcome (e.g., lung cancer), then attempt to match cases to individuals who do not have the outcome (controls). Work is done to look back to see if the exposure (e.g., smoking) is more frequent in the case group than the control group. Case control studies have several advantageous compared to other approaches: they are rapid to conduct compared to longitudinal studies (the event has already happened), and efficient because small sample sizes may be enough to reach conclusions. Among their limitations, however, is the problem of how to match cases with controls. Obvious matching accomplished by grouping by age categories, body mass index, gender, socio-economic status, and so on. Three papers authored by Wacholder published in American Journal of Epidemiology 1992 describe in detail, from theory to practice, case control selection (Wacholder 1992abc).

Randomized Control (interventional or experimental) Trials (RCT): compares an experimental treatment group with a control) placebo group. The groups are assigned to groups randomly. Another variant of a RCT is a randomized clinical trial, with the only difference that the clinical trial compares different treatments and may not include a control group.

Double-blind: The “gold standard” RCT. Both the patient and those interacting with the patient do not know what treatment the patient has received.

Placebo: a treatment in name only. The placebo is a designed but medically ineffective agent given to a study subject. There is considerable debate about what a placebo should contain and as to the ethics and general merits of its use in clinical trials (Temple and Ellenberg 2000).

- Active control or comparator studies are now common in place of placebo studies where treatment is clearly better than not giving the subject something of benefit (i.e., the placebo which is designed to not benefit the subject). Active control is not automatically a better choice than placebo control, because such studies may be less effective in evaluating cause and effect (Temple and Ellenberg 2000).

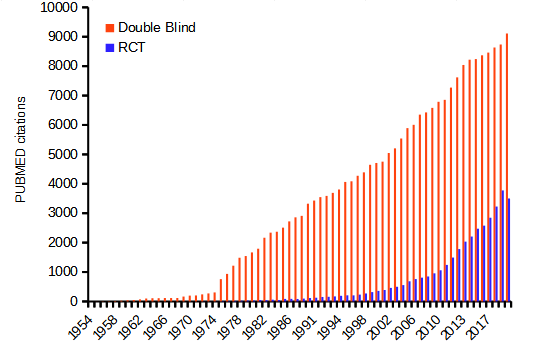

The controlled clinical trial has a long history: Daniel’s vegetarian diet (Daniel’s training in Babylon, Book of Daniel, Old Testament, discussed in Bhatt 2010, h/t Treece 1990) — after ten days those on Daniel’s diet looked healthier than the others who ate the King’s prescribed meal of meat and wine; James Lind’s scurvy trials on board HMS Salisbury, a British ship in 1747 (references in Bhatt 2010). Randomized control trials (RCT) were introduced by Hill and others in a 1946 study of streptomycin efficacy against tuberculosis. The effectiveness of RCT is now established and integral to regulation of drug development; see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). Use of clinical trials, unfortunately, has had a longer history than recognition of human rights. World War II Nazi medical research atrocities are well known (Berger 1990), so too the longitudinal study of Tuskegee syphilis study on African-Americans (Brandt 1978). But there are too many other examples: in 1884 Hawaii, the inoculation of Keanu by Dr. Arning with leprosy in exchange for commuting Keanu’s death sentence to life imprisonment (Keanu developed leprosy and died in 1890, Binford 1936); many studies of American Indians/Alaskan natives (Hodge 2012). Rules of conduct were established at Nuremberg, and subsequently extended and codified by the Belmont Accords: core principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. Ethical standards of who participates are institutionalized by IRB boards. True informed consent remains challenging (Rothwell et al 2021 and references therein).

Ethics of clinical and experimental research

Informed consent of subjects before proceeding in a clinical trial is a required, essential component of the design of a clinical trial. Guidelines for research conducted on human subjects originated from The Nuremberg Code (Shuster 1997). The Code was formulated 67 years ago, in August 1947, in Nuremberg, Germany, by American judges sitting in judgment of Nazi doctors accused of conducting torturous experiments on humans in the concentration camps (Shuster 1997). It served as a blueprint for today’s principles that ensure the rights of subjects in medical research. Achieving informed consent is not always straightforward (Nijhawan et al 2013), and we continue to see research that challenges ethical standards (e.g., discussion in Suba 2014). Additionally, and perhaps less appreciated, the Nuremburg Code is justification for invasive animal research: animal research must precede human subject testing (Shuster 1997).

While informed consent is required, clearly, it is not enough. Emmanuel et al (2000) provide a framework for evaluating the ethics of a research program involving human subjects:

- Value

- Scientific validity

- Fair subject selection

- Favorable risk-benefit ratio

- Independent review

- Informed consent

- Respect for enrolled subjects

An additional concept, clinical equipoise (Freedman 1987), is relevant. Freedman noted that the researcher must have “genuine uncertainty” with respect to the merits of each treatment, or an “honest null hypothesis.” If a consensus exists that one treatment is better than another, including placebo, then there is no null hypothesis and the research would be invalid (Emmanuel et al 2000). Take, for example, the suggestion that clinicians should withhold angiotensin-converting inhibitors (ACE2) from their hypertensive Covid-19 patients (Fang et al 2020; discussed in Tignaneli et al 2020). The hypothesis comes from the observation that SARS-COV2, like SARS-Cov, binds with ACE2 receptor in order to invade the cell. Blocking ACE2 inhibitors then would reduce activation of pulmonary renin angiotensin system and subsequent lung injury. Tignaneli et al (2020) called this a case of clinical equipoise — they argued no evidence supports “routine discontinuation” of ACE inhibitors.

Guidelines mandate detail about experimental design

Professional journals expect authors to provide detailed descriptions of all methodology, including aspects of experimental design. Fundamental to the aim of science, to increase our knowledge An essential component of science To improve this kind of communication many journals and professional societies have promoted standards about what must be included in these descriptions. For example, efforts of the CONSORT, which stands for CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials (www.consort-statement.org), to improve the reporting of clinical trials by authors and provide guidelines for reviewers and editors are endorsed by more than 400 journals. The CONSORT checklist addresses

- Trial design

- Participants

- Interventions

- Outcomes

- Sample size

- Randomization

- Implementation

- Blinding

- Statistical methods

These nine elements were judged essential for authors to report how their study implemented or did not implement. The purpose of these items is to in order to improve reproducibility of published research. For animal research, a similar list is available from ARRIVE (Kilkenny et al 2010). ARRIVE also addresses additional criteria and directs how these should be reported throughout the paper, not just in the methods section. Like CONSORT, hundred of journals have endorsed the ARRIVE 20-item checklist.

Clinical researchers must implement protocols to insure data management guidelines are followed. Clinical data management is a large topic in and of itself, so we won’t discuss this area further. However, good data management practice across disciplines share a number of features. For example, all data records should include metadata, where metadata refers to “information about data,” and would include enough information about the experiment, including

- dates and times of observations

- personnel

- facilities

- protocols used

- number of subjects

- list of variables with definitions

- full name of variable plus any acronym

- measurement units

- instrumentation

- notes about data quality

- conditions

and more (this is hardly an exhaustive list). Metadata therefore explains how data were obtained. Lists of variables are also called data dictionaries. If data are stored in spreadsheets, for example, then good practice includes including a worksheet with the metadata for the data set.

Questions

- Be able to define the following terms:

- case control

- case study

- cohort study

- cross sectional study

- observational study

- experimental study

- single arm trial

- single blind vs double-blinding in research design

- Early in the Covid-19 pandemic, hydroxycholoquine was suggested for treating Covid-19 patients, and some called for prophylactic use of the malarial drug. Discuss the treatment hypothesis in the context of clinical equipoise.

- Distinguish between case control prospective and case control retrospective studies, and the kinds of inferences that can be made from each.