12.4: Test of a Single Variance

- Page ID

- 26119

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A test of a single variance assumes that the underlying distribution is normal. The null and alternative hypotheses are stated in terms of the population variance (or population standard deviation). The test statistic is:

\[\chi^{2} = \frac{(n-1)s^{2}}{\sigma^{2}} \label{test}\]

where:

- \(n\) is the the total number of data

- \(s^{2}\) is the sample variance

- \(\sigma^{2}\) is the population variance

You may think of \(s\) as the random variable in this test. The number of degrees of freedom is \(df = n - 1\). A test of a single variance may be right-tailed, left-tailed, or two-tailed. The next example will show you how to set up the null and alternative hypotheses. The null and alternative hypotheses contain statements about the population variance.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Math instructors are not only interested in how their students do on exams, on average, but how the exam scores vary. To many instructors, the variance (or standard deviation) may be more important than the average.

Suppose a math instructor believes that the standard deviation for his final exam is five points. One of his best students thinks otherwise. The student claims that the standard deviation is more than five points. If the student were to conduct a hypothesis test, what would the null and alternative hypotheses be?

Answer

Even though we are given the population standard deviation, we can set up the test using the population variance as follows.

- \(H_{0}: \sigma^{2} = 5^{2}\)

- \(H_{a}: \sigma^{2} > 5^{2}\)

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

With individual lines at its various windows, a post office finds that the standard deviation for normally distributed waiting times for customers on Friday afternoon is 7.2 minutes. The post office experiments with a single, main waiting line and finds that for a random sample of 25 customers, the waiting times for customers have a standard deviation of 3.5 minutes.

With a significance level of 5%, test the claim that a single line causes lower variation among waiting times (shorter waiting times) for customers.

Answer

Since the claim is that a single line causes less variation, this is a test of a single variance. The parameter is the population variance, \(\sigma^{2}\), or the population standard deviation, \(\sigma\).

Random Variable: The sample standard deviation, \(s\), is the random variable. Let \(s = \text{standard deviation for the waiting times}\).

- \(H_{0}: \sigma^{2} = 7.2^{2}\)

- \(H_{a}: \sigma^{2} < 7.2^{2}\)

The word "less" tells you this is a left-tailed test.

Distribution for the test: \(\chi^{2}_{24}\), where:

- \(n = \text{the number of customers sampled}\)

- \(df = n - 1 = 25 - 1 = 24\)

Calculate the test statistic (Equation \ref{test}):

\[\chi^{2} = \frac{(n-1)s^{2}}{\sigma^{2}} = \frac{(25-1)(3.5)^{2}}{7.2^{2}} = 5.67 \nonumber\]

where \(n = 25\), \(s = 3.5\), and \(\sigma = 7.2\).

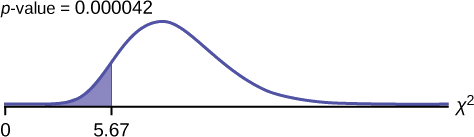

Graph:

Probability statement: \(p\text{-value} = P(\chi^{2} < 5.67) = 0.000042\)

Compare \(\alpha\) and the \(p\text{-value}\):

\[\alpha = 0.05 (p\text{-value} = 0.000042 \alpha > p\text{-value} \nonumber\]

Make a decision: Since \(\alpha > p\text{-value}\), reject \(H_{0}\). This means that you reject \(\sigma^{2} = 7.2^{2}\). In other words, you do not think the variation in waiting times is 7.2 minutes; you think the variation in waiting times is less.

Conclusion: At a 5% level of significance, from the data, there is sufficient evidence to conclude that a single line causes a lower variation among the waiting times or with a single line, the customer waiting times vary less than 7.2 minutes.

References

- “AppleInsider Price Guides.” Apple Insider, 2013. Available online at http://appleinsider.com/mac_price_guide (accessed May 14, 2013).

- Data from the World Bank, June 5, 2012.

Review

To test variability, use the chi-square test of a single variance. The test may be left-, right-, or two-tailed, and its hypotheses are always expressed in terms of the variance (or standard deviation).

Formula Review

\(\chi^{2} = \frac{(n-1) \cdot s^{2}}{\sigma^{2}}\) Test of a single variance statistic where:

\(n: \text{sample size}\)

\(s: \text{sample standard deviation}\)

\(\sigma: \text{population standard deviation}\)

\(df = n – 1 \text{Degrees of freedom}\)

Test of a Single Variance

- Use the test to determine variation.

- The degrees of freedom is the \(\text{number of samples} - 1\).

- The test statistic is \(\frac{(n-1) \cdot s^{2}}{\sigma^{2}}\), where \(n = \text{the total number of data}\), \(s^{2} = \text{sample variance}\), and \(\sigma^{2} = \text{population variance}\).

- The test may be left-, right-, or two-tailed.

Use the following information to answer the next three exercises: An archer’s standard deviation for his hits is six (data is measured in distance from the center of the target). An observer claims the standard deviation is less.